A proposed medical marijuana bill considers both suffering patients and a sick economy

Posted February 1st, 2010 by hiwayhowieNashville Scene: www.nashvillescene.com/2010-01-28/news/let-s-roll/·

Note: Howard’s comments appear about halfway thru this 3700 word article.

By Jim Ridley

Published on January 28, 2010 at 7:39am

Tucked away near a winding road in rural Maury County, the Santa Fe Diner is the picture of homespun Americana. It’s the kind of place where people get up to hold the front door for an elderly patron’s walker, where lifelong neighbors need only greet each other with a friendly nod. It’s Friday — fish day, as the flyer says under the wall-mounted photo of Santa Fe High School, class of ’56. On the front porch, an American flag flutters in a cold breeze while owner Carolyn Oakley prepares for the lunch rush.

The Santa Fe Diner and its proprietor are hubs of the community, as is clear from the cars filling the gravel lot, the photos on the walls and the warm greetings exchanged inside. But in the eyes of the state of Tennessee, and 36 other states, Carolyn Oakley is something else: an outlaw.

There has to be a good reason why an upstanding citizen would risk prison time and the loss of her belongings, including her business. Oakley’s reason slept next to her for 24 years. In the prime of life, her husband, Arthur Oakley, was stricken with a disease that shut down both his kidneys. He was immediately hospitalized, given shunts in his chest and placed on dialysis.

For two years, as he waited for a kidney transplant, Arthur suffered while his wife watched helplessly. He’d always been a hearty eater, but the powerful medicines he was taking killed his appetite. His weight dwindled. His blood pressure skyrocketed, which meant even more medicine. He became miserable, depressed. Eventually he refused to eat.

“It took away his want to live,” Oakley remembers.

After two years, Arthur was dangerously frail. In desperation, he and his wife talked to Bernie Ellis, a regular at the Santa Fe. It was known to some that Ellis, who had a 35-year career as a public-health epidemiologist, grew his own marijuana to relieve a painful spine and hip condition. It was also known he shared his stash free of charge with AIDS and cancer patients. Ellis volunteered to provide Arthur with free pot if his doctors agreed.

Their assent was hardly a sure thing. Medical marijuana remains a topic of intense, polarizing controversy in the medical field. Its status as a Schedule I drug — the harshest classification given to a narcotic, higher than cocaine or crystal meth — means that any doctor who prescribes it in a state without a licensed program runs the risk of prosecution. Indeed, when Arthur raised the issue early on with his first doctor, the reply was swift and strict: either no pot, or no kidney transplant.

His new doctors at Centennial Medical Center, however, saw that if he didn’t start eating again or reducing his dangerously high blood pressure, the kidney transplant would be a moot issue. According to Carolyn Oakley, they said that unless his health improved, he wouldn’t survive the surgery. They told the Oakleys, she says, to do whatever they needed to get Arthur eating again. Arthur went to see Bernie Ellis.

Once Arthur started smoking marijuana, Carolyn Oakley says, the change in his health was dramatic. Not only did his appetite return, she recalls, his nausea went away. His blood pressure subsided. In a particularly gladdening turn, so did his depression. Ellis hired Arthur to work outdoors on his farm and drive a tractor, something he hadn’t felt up to doing in years. “It made him feel like a man again,” Oakley says. Even above the clatter of plates in the back, the pride in her voice carries.

Arthur Oakley lived two more years, good years. In the end, he got his transplant, but a rare blood disorder caused his body to reject the kidney. In November 2003, he died of a heart attack. The service was held at a funeral home in Columbia, and the Oakleys’ neighbors and the Santa Fe Diner’s regulars crowded into the chapel.

Among them was Bernie Ellis, whose own fortunes had undergone a drastic turn in the intervening years. In 2002, drug agents on ATVs and in helicopters stormed his farm in the nearby community of Fly. According to a tactical field report, agents found some 537 marijuana plants, a number that was amended for unknown reasons a month later to 300. Ellis puts the actual number of mature, full-size plants closer to a couple dozen, but no matter — even that was enough to raise the prospect of hard time and losing his farm.

To avoid the worst-case scenario, Ellis pleaded guilty in late 2003 to manufacturing cannabis plants. He later tried to withdraw the plea, but with no success. When he walked into the funeral home, then, everyone in the close-knit community had to know he had admitted publicly to a felony.

What trumped that, though, was that they knew what he had done for Arthur Oakley. Carolyn Oakley recalls that even Enoch George, the Maury County sheriff, stopped to shake Ellis’ hand as mourners filed from the chapel. To this day, over the corner table in the Santa Fe Diner where Oakley sits with a reporter, a framed Scene cover calling Ellis the “Marijuana Martyr” occupies a place of pride. If there’s any stigma attached to medical marijuana, Oakley hasn’t seen it.

“I haven’t lost the first customer because of it,” she says, her voice firm.

It’s because of stories like Carolyn Oakley’s, proponents of medical marijuana say, that a sea change in attitudes toward the issue is under way. Two decades ago, it was easy to dismiss medical-marijuana advocates as a fringe element — stoners trying to sneak legalization past the nation’s drug-enforcement gatekeepers. Got a hangnail that’s bothering you? Whatever you say, Cheech. Coming right up.

Today, though, millions of people are only a degree of separation from someone whose all-too-real suffering has been eased by cannabis. So what if medical marijuana were a business — an above-ground, state-sanctioned business that could funnel millions of dollars into Tennessee’s economy, under the oversight of local law enforcement and the state agriculture and health departments?

That’s the remarkable proposal coming up for review in the Tennessee legislature this session. A bill introduced Jan. 13 by Sen. Beverly Marrero in the state Senate and Rep. Jeanne Richardson in the House — SB 2511/HB 2562, aka the Safe Access to Medical Cannabis Act — provides a blueprint for implementing a statewide medical marijuana program from seed to flower.

The Memphis Democrats’ bill proposes nothing less than licensing local farmers, cultivating cannabis at strongly restricted compounds, and selling prescribed doses of high-grade marijuana through pharmacies — at a low price specifically designed to benefit the sick and undermine illicit dealers. If enacted, it would be on arrival the most tightly controlled of the 14 state-run medical-marijuana programs either under way or in development in the U.S. It would also be the most patient-friendly.

In a stroke of irony, the proposal’s architect is none other than Bernie Ellis, who has a distinguished track record assisting states such as Wyoming and New Mexico devise and manage substance-abuse programs. This is not a substance-abuse issue, Ellis says. This is about restoring marijuana to its rightful place in the arsenal of modern medicine.

“It’s the safest therapeutic substance known to man,” Ellis says.

To pass, the bill will have to clear hurdles that would make an Olympian shudder, which only start with the partisan rancor and hard conservative shift of Tennessee’s legislature. Tougher still, there’s the matter of marijuana’s Schedule I classification — which maintains, despite the evidence of the nation’s eyes and ears, that pot is more dangerous and has less medical benefit than crack cocaine. Changing that classification will require the federal equivalent of plate tectonics.

“From our standpoint, law enforcement should be happy because we’re [proposing to take] the demand for medical marijuana off the street, take money and power away from illegal dealers and put them in the hands of the people,” says Rose Cox, a lobbyist and 13-year political operative with a background in health care lobbying, who has been hired by NORML to push the medical-marijuana effort in the Tennessee legislature. Still, she concedes there’s “a healthy amount of skepticism on both sides” and major concerns about federal law.

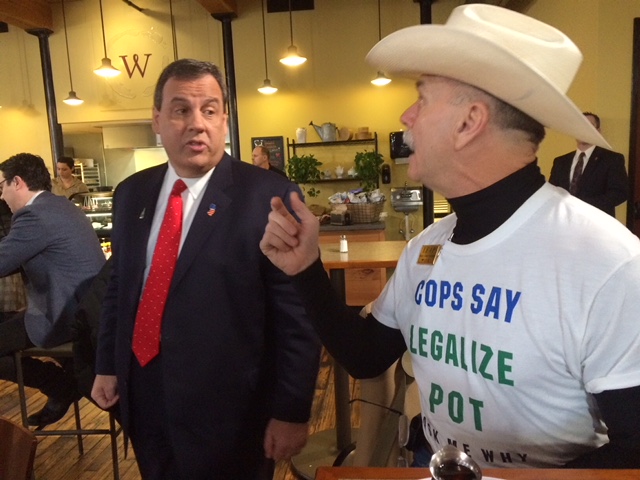

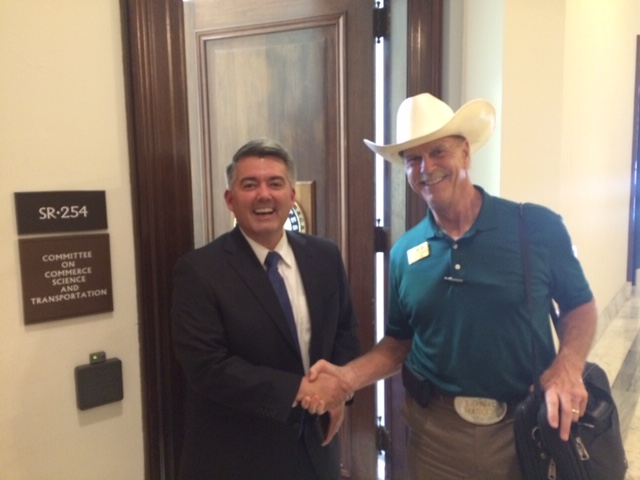

Yet Howard Wooldridge, a Washington drug policy specialist who co-founded the group Law Enforcement Against Prohibition (LEAP) and now directs Citizens Opposing Prohibition (COP), believes the timing has never been better for a serious consideration of medical marijuana. The tipping point came late last year, he says, when the Department of Justice issued a directive instructing federal prosecutors not to go after participants in state-sanctioned medical-marijuana programs, ostensibly to conserve government resources. Independently, the powerful American Medical Association reversed its long-standing support of the Schedule I classification, indicating that cannabis held promise for medical research.

Why the shift? Wooldridge, who served for 18 years as a Michigan law-enforcement officer, believes that the current generation in power (many of whom came of age in the 1960s and early ’70s) is rediscovering marijuana as a medicine after years of post-college abstention. They know from their own experiences that one puff of weed does not an addict make. Furthermore, the anecdotal evidence of marijuana’s medicinal properties — not to mention the many polls showing wide margins of support for doctor-patient medical-marijuana treatment — is by now too overwhelming to ignore.

“The current economic crisis combined with the generational shift will move drug prohibition into the history books in five years,” Wooldridge predicts.

The anecdotal evidence today isn’t just coming from the expected quarters. It’s coming from die-hard conservatives with anything but love for the Obama administration. It’s coming from physicians who have seen gravely ill patients respond to a substance they can’t legally study, let alone prescribe. It’s coming from the families of lawmakers, some of whom maintain a public stance against the issue.

Perhaps most importantly, it’s starting to come from ordinary voters who never had a stake in the issue before, but have experienced firsthand an improvement in a loved one’s quality of life — or their own.

Dozens of people sent testimonials along those lines to U.S. District Judge William Haynes when he was weighing Bernie Ellis’ sentence in 2005. Mrs. Ellen Humphrey, a woman who’d been Ellis’ neighbor for 34 years, watched her husband Junior wither from lung cancer; the nurses at his Columbia care facility suggested he get some marijuana post-haste. “The marijuana Bernie Ellis provided … made it possible for Junior to rest and to sleep,” she wrote, “and it helped him keep his appetite up.” G.A. Webber, then a 35-year-old man living with AIDS, wrote that he used marijuana to alleviate nausea from his anti-HIV medicines and pain from a dual hip replacement.

Mrs. Margie Aderhold, an ovarian-cancer survivor, put the matter bluntly to the presiding judge. “Before you pass judgment,” she wrote, “please consider how you would feel if your own parents or children (or you yourself) were dying from a disease and could be helped to live longer or in less pain by using marijuana.”

In the end, Ellis received a four-year probation sentence (later reduced to two years) and was forced to surrender 25 acres of farmland to the federal government, ending a seven-year ordeal. The same legal nightmare could easily have happened to Carolyn Oakley. But the plain-speaking woman with the straight brown hair and no-nonsense manner says the threat of losing her freedom and her diner never deterred her from helping her husband.

“If we lose the business,” she remembers telling their grown children, “we don’t need it no way.”

Now there is the chance for Tennessee to legally relieve the suffering of terminal patients and the severely ill, while shoring up rural communities, making real headway in the drug war and channeling new money into the state’s coffers. All it will take is reversing almost a century of demonization that has cast marijuana as Public Enemy No. 1, not a healing agent with untapped potential.

For such a volatile issue, medical marijuana is hardly new. According to a 2001 book called Marijuana and Medicine: Assessing the Science Base produced by the National Academy of Science’s Institute of Medicine (IOM), it dates back at least to the Chinese emperor Chen Nung some 27 centuries before the birth of Christ. The book also reproduces labels that show the U.S. pharmaceutical giant Eli Lilly was manufacturing and selling a marijuana tincture throughout the 1930s.

But by 1942, marijuana had been removed from the United States Pharmacopoeia, the standard-setting volume for medicines and dosages, on grounds that it was a dangerous drug. Thanks to its association with black jazz musicians on one hand and Mexican immigrants on the other — and exacerbated by the U.S. government’s frankly racist propaganda — cannabis became linked in the public mind with evils ranging from race-mixing to homicidal frenzy. The 1936 scare film Reefer Madness remains an unforgettable artifact of wacky-weed hysteria, with its squeaky-clean teens turned pinwheel-eyed dope fiends. A year later, the plant was effectively outlawed.

In 1970, as the Nixon administration shook its fist at the counterculture, the U.S. government created the landmark Controlled Substance Act. The act created five classifications for controlled substances, weighing their health benefits against their addictive power and potential for harm. Tobacco and alcohol do not appear on the lists, but covered substances range from cough syrup (Schedule V) to oxycodone (Schedule II). Among those that made it all the way to Schedule I, the most restrictive ranking, were heroin, LSD — and marijuana.

For four decades hence, that classification has dominated policy on marijuana. But some states in the 1970s and ’80s passed laws that either lowered marijuana’s ranking or paved the way for clinical testing. A bill signed into law in 1984 by then-Gov. Lamar Alexander even allowed for medical marijuana in Tennessee, although the law was repealed in 1992 when thousands of AIDS patients nationwide applied to their states’ programs and the federal government stopped supplying the medicine.

In the years since, however, 14 states and the District of Columbia have said yes to medical marijuana, the majority through popular ballot initiatives that won by wide margins. That has typically put the states at odds with the federal government, which has claimed precedence over local measures — one reason last fall’s Department of Justice directive was seen as a breakthrough.

TBI special agent in charge T.J. Jordan cautions that the DOJ directive is hardly set in stone. He’s part of the administrative side of the Governor’s Task Force on Marijuana Eradication, a task force composed of the TBI, the Tennessee Highway Patrol, the Tennessee Alcoholic Beverage Commission and other agencies. Since 1983, it has become one of the top six outdoor-cultivation eradication programs in the U.S., destroying some 400,000 marijuana plants last year at an estimated street value of $320 million. If medical-marijuana advocates are pinning their hopes to the policy directive, the agent asks, what happens if the next elections don’t go their way?

“That’s today’s administration’s policy,” says Jordan, who expresses concerns about just what the law-enforcement oversight in the Safe Access bill entails. “What’s the next administration’s policy?”

If the medical-marijuana movement were just a ploy to get access to pot, chances are that it would have gained little traction. Howard Wooldridge says that when he addresses Rotary groups on the topic, as he has done more than 400 times, their overriding concern is, “Will drug use skyrocket?” (The short answer, according to available data, is no.) But the cause has been helped enormously in recent years by doctors, scientists and medical researchers, who would seem to have proved to even the most calcified skeptic that the plant has properties worth researching.

According to Sunil Aggarwal, a University of Washington M.D./Ph.D. candidate who has co-authored several papers summarizing the many medicinal uses of cannabis, some of the many complex chemical compounds found in marijuana (known as “cannabinoids”) have shown promising effects in treating neurological disorders. These include multiple sclerosis, Lou Gehrig’s disease (or ALS), Alzheimer’s disease and certain forms of brain tumors.

Still more scientific evidence suggests marijuana may work well in tandem with other treatments — reducing the gut-wrenching side effects of chemotherapy, for example, or the lack of appetite caused by some anti-HIV drugs. From glaucoma to rheumatoid arthritis, from hepatitis C to osteoporosis, enough evidence of marijuana’s potential for good exists that a growing number of doctors agree the plant deserves further study.

“A huge policy shift is happening,” says Aggarwal, who believes “an emerging consensus in the medical community” wants to see marijuana downgraded from Schedule I so earnest research can begin. That doesn’t sound like such a controversial position. Right?

Ask the American College of Physicians. A prominent physicians’ group second only in size to the AMA, the ACP issued a position paper last year that called simply for revisiting the Schedule I classification.

From the response, though, the august body might as well have recommended firing up a doob during open heart surgery. Dr. J. Fred Ralston, the Fayetteville physician who serves as the ACP’s president-elect, says some marijuana advocates and opponents alike misconstrued the paper to fit their agendas. In the ensuing shouting match, he says, they obscured its reasonable, thoroughly middle-of-the-road call for more research.

“I think you can make an argument both ways,” says Ralston with caution, explaining he has no position on the bill in the legislature. “This is a hot-button issue, and we had a very narrowly focused paper that said we are never against more investigation.”

At the same time, Aggarwal says, the significance of the AMA and ACP’s new positions should not be underestimated.

“When the two largest medical organizations in the U.S. independently arrive at the evidence-based conclusion that marijuana’s status as a Schedule I drug should be seriously reconsidered,” he wrote in an opinion piece on the pain-management website Pain.com, “federal drug regulators should take note.”

On one point, though, many medical-marijuana advocates and opponents agree: They don’t want Tennessee to have a program like California’s. Voted in by ballot measure under Proposition 215 in 1996, California’s laissez-faire program has become an out-of-control system where almost anyone can be a patient, any patient can be a grower, and dispensaries range from sedate waiting rooms to jokey clubhouses with bud menus and T-shirts.

Critics say it’s essentially back-door legalization — which is exactly what many users love about it. A Nashville musician who has purchasing privileges in California says it was “laughably easy” to obtain his prescription, and easier still to buy the actual weed, available in strains of different potency. (Try the purple, he says.)

But Ellis, hardly a prude on the subject, disdains the California model for several reasons. One is what he calls a “wink-wink-nudge-nudge” flippancy that has made the program a punchline, damaging its credibility. Another is the uneven potency, which renders dosages unpredictable and hence less effective as medicine. Then there’s the price: sometimes as much as $80 per eighth of an ounce, comparable to street value. For people hit with catastrophic medical expenses, Ellis says, that price is “unconscionable.”

What Ellis favors, as proposed in the pending bill, is a fire-sale price of $60 per ounce — a staggering cost cut that’s cheap enough for hard-hit patients, yet costly enough to yield a significant return to the grower, the state and the pharmacy. (The bill envisions a split of $30 per ounce to the licensed farmer, $10 to the pharmacy and $20 to the state to cover the cost of implementation, with excess state revenues going to fund indigent health care and substance-abuse treatment.)

Tennessee’s program would be far more strict in many ways, from qualifying illnesses (a list of 12 life-threatening or severely painful conditions) to specifications for growing, processing and packaging the medicine and regular law-enforcement oversight. Nevertheless, if 150,000 people — an estimated 15 percent of Tennessee’s current cannabis users — were to sign up, such a program could be grossing $450 million a year in three years’ time.

Is safe access to state-regulated medical marijuana a pipe dream in Tennessee? Perhaps. “I doubt that Tennessee will be on the vanguard of any change,” Dr. J. Fred Ralston says. So far, no Republican has stepped up as co-sponsor, but Sen. Marrero sees no reason why one wouldn’t.

“Just look at all the fuss over health care,” says Marrero, whose son-in-law benefited from medical marijuana when he underwent chemo and radiation treatment for cancer years ago. “All you hear about is the fear that some bureaucrat will come between you and your doctor — well, this is a pretty clear case of that. Our bill specifies that the medicine would only be available with a doctor’s prescription and can only be purchased in a pharmacy, but for some reason some people think the government knows better than the doctors and pharmacists. Frankly, passing this bill is going to require legislators of both parties with the courage to do the right thing.”

“Politicians will eventually get hurt by not supporting it,” says Paul Kuhn, a veteran Nashville investment counselor who is both a longtime Republican and a longtime supporter of NORML. His belief in medical marijuana was cemented when Jeanne, his wife of 31 years, was diagnosed with breast cancer in the mid-1990s. She was 4-feet-11½, and the chemotherapy poisons pumping through her took a heavy toll. Never a pot smoker herself, she found that marijuana was the only thing that helped her through grueling rounds of chemo. The marijuana gave her comfort until she succumbed to cancer in 1996.

“I just smell marijuana and it reminds me of chemo,” Jeanne once said wearily. But after trying yet another inefficient dose of conventional medicine, she would say, “Bring me the damn pot.”

In preparation for a particularly agonizing treatment, she once went so far as to show up at Saint Thomas Hospital with a one-hitter pipe. Nurses were flustered. Additional personnel were called. The Kuhns stood firm. Someone with ultimate authority had to be consulted. A call was placed upstairs, Kuhn says, to the hospital’s chief legal counsel.

The answer came back: It was in the patient’s best interest.